Cats have padded silently through human history, leaving paw prints not only in homes and temples but also in myths, languages, and empires. Ever mysterious yet ever present, they have accompanied us as hunters of pests, companions of deities, and even mascots of soldiers on campaign. When we trace their story from the banks of the Nile to the forums of Rome, we see how these sleek and self-reliant creatures came to embody everything from fertility and wisdom to freedom and independence. This is the tale of how cats conquered the ancient world.

Origins in Ancient Egypt

Few cultures granted cats more honor than ancient Egypt. They were sacred to the goddess Bastet, often depicted with a feline head, who embodied both domestic warmth and divine mystery. Cats were so valuable that Egypt passed laws forbidding their export. This was not only a strategy to protect sacred animals but also an acknowledgment of their importance to agriculture and daily life. Cats preserved grain stores by hunting vermin, and their presence carried spiritual weight.

Yet, like cats themselves, rules could not keep them confined. Merchants, sailors, and perhaps a few smugglers ensured that felines slipped across borders, beginning their long association with human movement and trade.

Further reading: Cats in Ancient Egypt: From Mouse Hunters to Divine Beings

Phoenician Traders and the Spread Across the Mediterranean

The great seafaring Phoenicians, masters of Mediterranean commerce, became some of the first international ambassadors for the feline race. Cats, admired for their elegance and usefulness, traveled aboard ships either by purchase, barter, or as stowaways. From these decks, whiskers peeked at new coastlines, and paws crossed into cultures far from the Nile Valley.

Their arrival abroad did not please the Egyptians, who occasionally repurchased cats from foreign lands in an attempt to bring them home. But the tide of history, like feline independence, proved unstoppable. Within a few centuries, cats were clawing a new identity among Europeans, especially the Greeks.

The Greeks: From Myth to Daily Life

Around the 5th century BCE, cats reached Greece. Here they were welcomed as graceful hunters who kept food stores safe from rodents. The Greeks admired their cleanliness and composure, qualities that perfectly matched a society embracing balance and beauty.

The Greek word for cat was ailouros, meaning “with a twitching tail.” Language captured what everyone notices about felines: their constant, restless movement and the expressive flick of their tails.

Cats soon became more than pest controllers. They entered the Greek imagination, slipping into religious symbolism and local stories, often tied to existing deities.

Cats in Greek Mythology

The Greeks practiced cultural translation, aligning foreign gods with their own. When they encountered the Egyptian goddess Bastet, they saw in her traits resembling Artemis, goddess of the hunt, the moon, and chastity. Cats, nocturnal hunters linked to lunar cycles, fitted Artemis’ qualities well. The irony was that the Egyptians never tied their cat goddess to virginity, whereas the Greeks stretched connections to fit their divine narratives.

Artemis was honored with one of antiquity’s greatest temples at Ephesus, renowned as a Wonder of the Ancient World. Some statues of Artemis from Ephesus bear dozens of breasts, expressing fertility, yet intriguingly, a few also display feline imagery. In these, cats themselves carry human-like breasts, an odd but telling example of myth blending sexuality, fertility, and animal symbolism.

Athena, the goddess of wisdom, is usually associated with the owl, yet feline links appear in regional cults. Known as Athena Glaukopis, “bright-eyed,” she evoked the haunting nighttime gaze of a cat. Unlike owls, whose eyes do not glow, cats possess a reflective layer behind the retina. The glint of feline eyes shone like divine wisdom in the dark.

Hekate, goddess of the underworld and crossroads, made the feline connection even clearer. She was sometimes believed to take the form of a black cat, embodying mystery, liminality, and danger. Here the cat’s nocturnal wanderings aligned perfectly with Hekate’s realm.

Thus, cats in Greece navigated both myth and reality, much like they do today, inhabiting hearths but retaining an aura of magic.

Roman Perspectives: From Skepticism to Symbolism

When cats padded into Roman lands, they faced a culture more enamored with dogs. Romans valued loyalty, discipline, and obedience, qualities not usually associated with cats. Cats, however, embodied something Romans also admired: freedom and independence.

The goddess Libertas, symbol of freedom, was often depicted with a cat at her feet. In catlike fashion, the animal flipped expectations, reminding Romans that independence, though inconvenient, was also noble.

Roman writers and artists layered new meanings onto the feline. Ovid, in his Metamorphoses, described gods fleeing to Egypt during a cosmic war and donning animal forms for disguise. Diana, the Roman face of Artemis, chose the guise of a cat. Across frescoes and sculptures, Diana sometimes stands with cats at her side, blurring divine dignity and domestic companionship.

Cats in Roman Religion, Literature, and Popular Culture

The Romans, both scandalous and witty, applied feline imagery in playful, even risqué ways. The dramatist Plautus coined the term feles virginaria, literally “cat of the maidens,” which he twisted to mean a tomcat of a rather different sort: a human male seducer. Other plays joked about feles pullaria, “cat of young girls,” again hinting at men who lured women like cats stalking prey.

Venus, goddess of erotic love, was occasionally portrayed with a cat, connecting feline moodiness with the unpredictable power of desire. Anyone who has loved either a person or a cat could recognize the metaphor.

Not all associations were sensual. Roman naturalists like Pliny the Elder recorded medical uses for cats that strike modern readers as bizarre. He claimed ashes of cats warded off mice when sprinkled on seeds, though he admitted the smell could linger unpleasantly in bread. Even cat urine, excrement, and organs found their way into so-called cures. Distasteful as these remedies sound, they reveal how cats entered not just homes and temples but also the pharmacopoeia of antiquity.

Felines on the March: Soldiers, Ships, and Empire

For practical Romans, cats were indispensable companions on campaign. They marched with legions, guarding food from rodents. Archaeological remains of cats have been uncovered at fortresses from Britain to North Africa. Their pawprints, literally and figuratively, followed armies into every outpost of the empire.

Roman naval power carried cats farther still. They were mascots of ships, considered bringers of luck. Many vessels bore the name of Isis, the Egyptian goddess linked with cats and sailors’ protection. Carved cats commonly graced ship prows, gazing forward into unknown waters. Through maritime trade cats traveled along the Silk Road into Persia, India, and eventually East Asia.

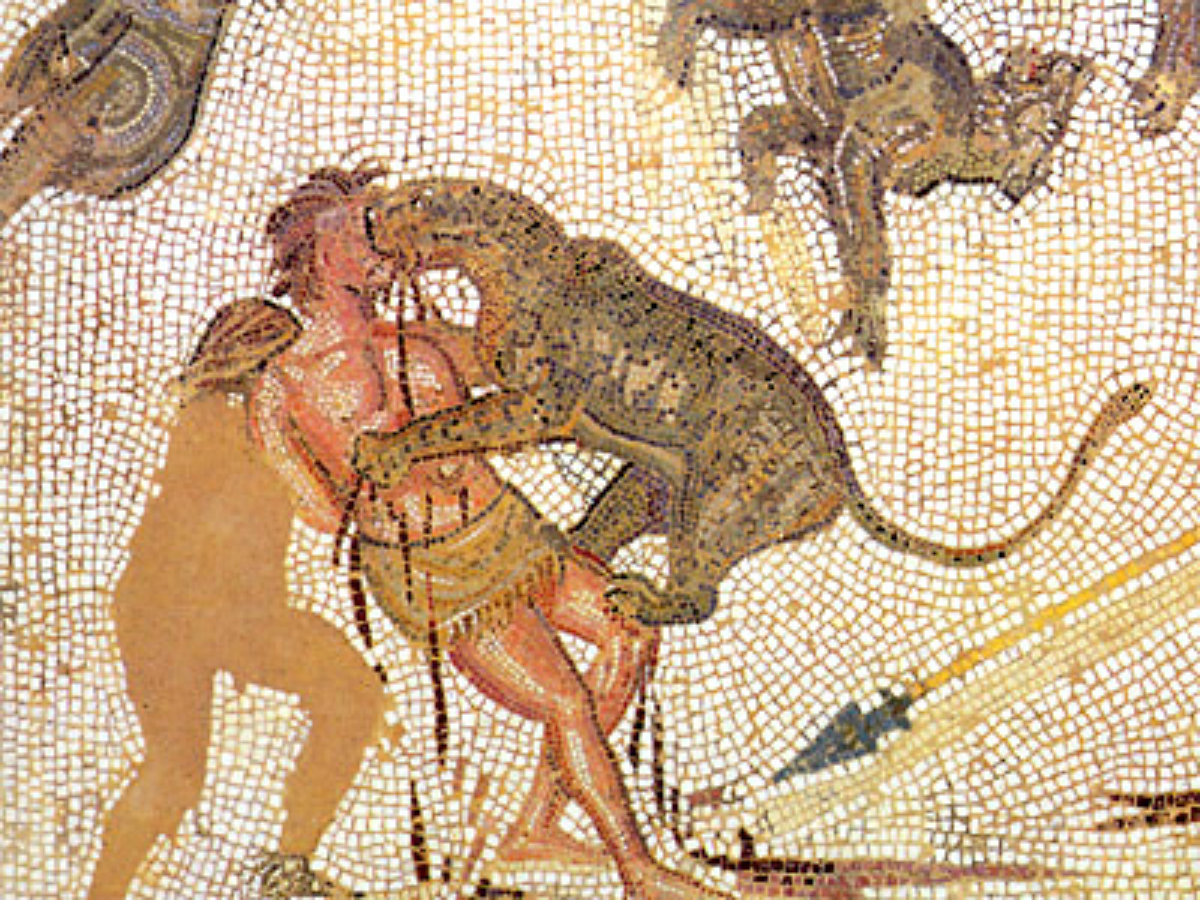

Military banners even displayed cats as emblems. Records tell of a cohort who painted a running green cat on their shields, its head turned in alertness, and of another unit, the Felices Seniores, depicting a vigorous red cat reaching to seize its prey. Tough soldiers, it seems, saw no shame in carrying feline symbols. Instead, they admired sleekness, agility, and deadly precision.

Art, Archaeology, and Legacy of Cats in Antiquity

Roman artisans ensured cats were immortalized in mosaics, statues, and household items. In Pompeii, cats appear attacking birds across elaborate floor scenes, frozen in a predator’s eternal moment. In one poignant discovery, the skeletal remains of a woman were found cradling a cat, suggesting bonds of affection that transcended disaster.

Elsewhere, mosaics from Jordan to Morocco featured cats in dramatic encounters with mice, birds, and fish. One mosaic names the cat “Vincentius,” meaning “Conqueror,” showing it dispatching a mouse called “Luxurius.” The humor is unmistakable—a reminder that even then people enjoyed attributing personalities and names to their feline companions.

Even decorative furniture bore images of cats, like a French table support carved with a boy cuddling a collared and belled feline. Such images are not just artistic motifs but glimpses into the intimacy people felt toward cats long before they were universal house pets.

Linguistic evidence echoes this legacy. Latin gave us feles, later replaced by cattus, likely drawn from African tongues. From this root came cat, katze, gato, chat, katt: the familiar global words we use today. Each language preserved the memory of ancient Rome’s linguistic inheritance, spoken every time a name is called at the kitchen door.

The Timeless Cat

From Egypt’s temple guardians to Rome’s military mascots, cats carved a unique role in the ancient Mediterranean world. They fought pests, symbolized freedom and love, and inspired myths that placed them among gods. Independent yet close, practical yet sacred, cats revealed the contradictions of the societies that embraced them.

Today when a cat curls lazily in a sunny window or narrows its luminous eyes in the twilight, it recalls generations of ancestors who crossed seas and empires. Their journey from Bastet’s shrine to Caesar’s legions mirrors the cat’s own nature, simultaneously aloof and indispensable, ordinary and divine.

It is no wonder that they remain humanity’s enigmatic partners, commanding affection while never entirely yielding to control. The ancient world may have passed, but the cultural reign of the cat continues with every soft paw and watchful gaze.

Photo by Fatih Doğrul.