The creak of wooden decks underfoot, the salty spray of the Atlantic whipping through fur, and tiny kittens mewling in the shadows of vast sails set the scene for an extraordinary chapter in feline history. In an era when Britain’s navy ruled the waves, domestic cats became unwitting explorers, hitching rides on ships that reshaped the world. These felines, known scientifically as Felis catus, transformed from ancient Egyptian companions into essential crew members, spreading far beyond their Old World origins through human ambition and maritime might.

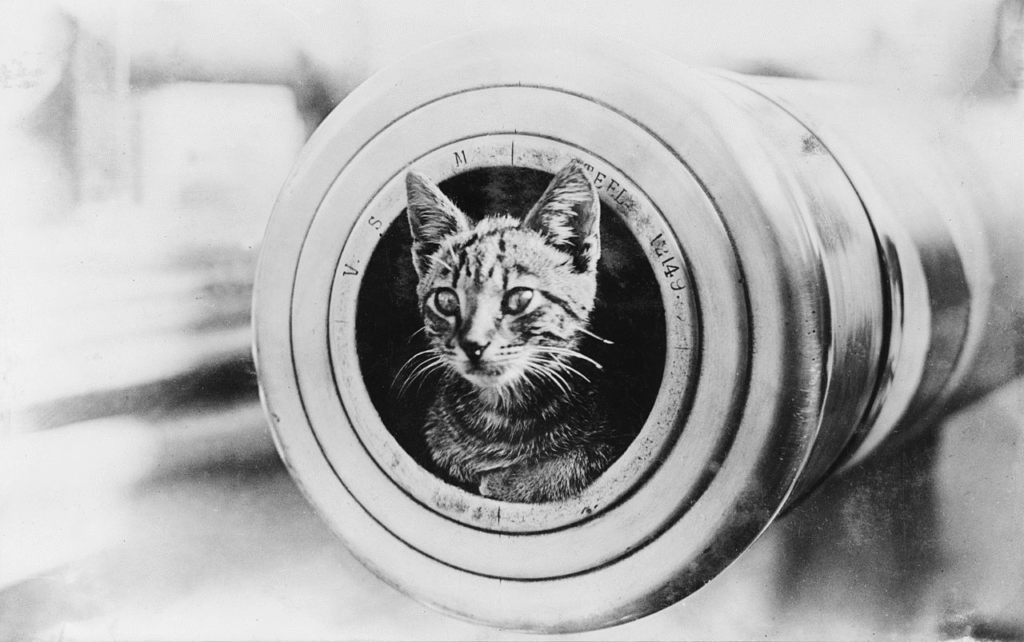

During the height of Britain’s naval dominance in the 16th and 17th centuries, cats boarded British vessels as indispensable allies against the ever-present threat of rodents. Rats and mice gnawed through ropes and devoured provisions, turning long voyages into potential disasters, so sailors welcomed cats for their hunting prowess. On these transatlantic crossings to the New World, the journey often lasted months, giving cats ample time to birth litters in the dim holds below deck. As ships docked in bustling harbors like those of the early English colonies, young cats scampered ashore, either leaping overboard in curiosity or being traded among settlers eager for their pest-control skills. Native Americans, who knew only wild felines like the bobcat resembling the American lynx, encountered these tame newcomers with a mix of awe and intrigue, marveling at creatures so similar in appearance yet astonishingly docile.

Settlement in the Americas brought cats into the heart of colonial life, where their practical role shone brightest. In places like Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent English colony founded in 1607, cats guarded meager food stores against invasive pests that arrived with the Europeans. Yet survival hung by a thread during the brutal winter of 1609-1610, forever etched in history as the “Starving Time.” A severe drought had scorched the fields, trade with Indigenous peoples faltered, and supply ships failed to arrive, leaving over 500 colonists to face famine with mouths far outnumbering rations. Desperation peaked as settlers burned homes for fuel and traded tools for scraps of corn, their bodies weakened by scurvy and despair. In this grim tableau of skeletal figures huddled in mud-churned streets, even beloved animals fell victim; archaeological digs have unearthed bones of cats, dogs, and horses mingled with rat remains in trash pits, proof that colonists consumed their feline protectors to stave off death. One poignant case involved the butchered remains of a teenage girl, her skull marked by cuts mirroring those on animal carcasses, underscoring the horror that spared no one, not even the cats once valued as lucky charms.

Despite such tragedies, cats proved resilient, carving out niches in the expanding frontier. As English settlements pushed westward, felines tagged along with pioneers, fortifying garrisons and outposts in the untamed wilderness. By the mid-19th century, during the California Gold Rush, miners transported cats overland and by sea to boomtowns teeming with opportunity and infestation. In Alaska’s icy outposts, these travelers fetched prices in gold dust, their rodent-hunting reputation preceding them like a badge of honor. Soldiers stationed at remote Kansas forts in the 1850s relied on them too, hoping to curb the mouse plagues that plagued barracks. But not all cats embraced their duties with zeal; an army sergeant lamented how the felines there turned into “total wrecks,” too overwhelmed by fleas to hunt effectively, instead waddling about in defeat. Some, it seems, abandoned the flea-ridden human camps altogether, venturing into the vast prairies where native prey like rabbits and birds offered easier meals and freedom from expectation. This subtle rebellion highlighted the dual nature of the human-cat bond: cats served humans when it suited them, but their wild instincts always simmered beneath the surface.

Beyond the practical, cats wove into the symbolic fabric of colonial society, embodying both fortune and fear. Superstitions trailed them across the ocean, rooted in European folklore where felines linked to witchcraft and the supernatural. In the infamous Salem witch trials of 1692, accusers claimed the suspects could shapeshift into cat-like forms, fueling paranoia in the Puritan settlement where shadows of black cats evoked demonic pacts. Such tales painted cats as enigmatic bridges between worlds, companions in daily toil yet harbingers of mystery in the flickering candlelight of log cabins. Their presence offered comfort amid isolation, a soft purr against the howl of wilderness nights, even as myths cast long shadows.

The cats’ odyssey extended southward to Australia, where British convict ships and colonist vessels carried them in the late 18th century. On these cramped decks, felines dodged the chains of prisoners while pursuing rats through the bilge water. Upon arrival in Sydney Cove in 1788, cats disembarked into a land devoid of their kind, quickly adapting to eucalyptus groves and coastal scrub. Indigenous Australians, the Aboriginal peoples with deep ties to their environment, met these intruders with wonder during early encounters. In 1823, aboard the HMS Mermaid anchored off Queensland, colonial official John Uniacke observed Aboriginal visitors boarding the ship, their eyes wide at the sight of cats for the first time. They stroked the animals endlessly, hoisting them high to show companions onshore, filled with a special astonishment at these soft, purring beings unknown to their ancient stories.

This fascination rippled across the Pacific islands, where Polynesian communities traded eagerly for the newcomers. American explorer Titian Peale noted a “passion for cats” among Samoans in the 1840s, who bartered fiercely with whaling ships to acquire them. On Ha’apai in Tonga, locals once swiped two of Captain James Cook’s cats during his 1770s voyages but returned them after second thoughts, a mix of mischief and respect. Further afield on Eromanga in Vanuatu, islanders exchanged fragrant sandalwood cords for explorer cats, valuing the animals as treasures from distant seas. One standout voyager captured hearts worldwide: Trim, the black-and-white ship’s cat of Captain Matthew Flinders. Born in 1799 aboard HMS Reliance en route to Botany Bay, Trim survived a dramatic fall overboard, swimming back and scaling a rope to rejoin the crew, earning Flinders’ eternal admiration. Together, they circumnavigated Australia from 1801 to 1803 on HMS Investigator, with Trim perched at the captain’s table, batting at forks and studying the wildlife with keen eyes. Flinders’ log brimmed with affection, detailing Trim’s “numerous and curious observations” on small mammals, birds, and flying fish, subjects he pursued with endless curiosity. Even after a shipwreck on the Great Barrier Reef in 1803, where Trim buoyed stranded men’s spirits, and during Flinders’ six-year imprisonment in Mauritius, the cat remained a faithful sidekick until his mysterious disappearance in 1804, possibly at the hands of a hungry local. Today, a bronze statue of Trim graces Sydney’s waterfront, a testament to his legendary status.

By the 1840s, some Aboriginal people carried kittens in pouches like cherished accessories, echoing modern pet culture, and by century’s end, cats blended into the Australian landscape as quasi-native dwellers. These cross-cultural exchanges revealed cats’ magnetic pull, turning strangers into admirers overnight. In Indigenous villages, where smoke from campfires curled into starry skies, a cat’s gentle nuzzle sparked joy, bridging divides forged by conquest.

Cats needed no formal invitation to thrive; wherever they landed, they touched down on all fours, embodying adaptability. From the teeming ports of the Americas to the sun-baked shores of Australia, they infiltrated nearly every major landmass by the mid-19th century, their populations exploding unchecked. This quiet conquest mirrored humanity’s own expansions, with cats as sly co-pilots in the age of empire. Yet, the tradition of ship cats faded in the 20th century, culminating in 1975 when the British Royal Navy banned them aboard vessels, citing rabies risks in an era of modern pest control and health protocols. Still, their legacy endures in the global feline family, a reminder of resilience forged on rolling seas, where paws and sails charted paths to new horizons.